Glass is undoubtedly one of humanity’s most favoured materials. It’s everywhere.

We use it to see, to drink from, to store food. It’s used in jewellery, in surgical

equipment, in the screens of our devices. It magnifies, it traps heat, it transmits

light… you get the picture.

Humans have found ways to manipulate this material for all of these different uses.

Even our earliest societies like the Ancient Egyptians, the Mesopotamians and the

Phoenicians experimented with shaping glass into beads and ornaments. Today,

technological advances have multiplied its uses. What began as trinkets and

jewellery has transformed into an industrial material used in our windows, walls,

doors, cars and more. Quite the journey!

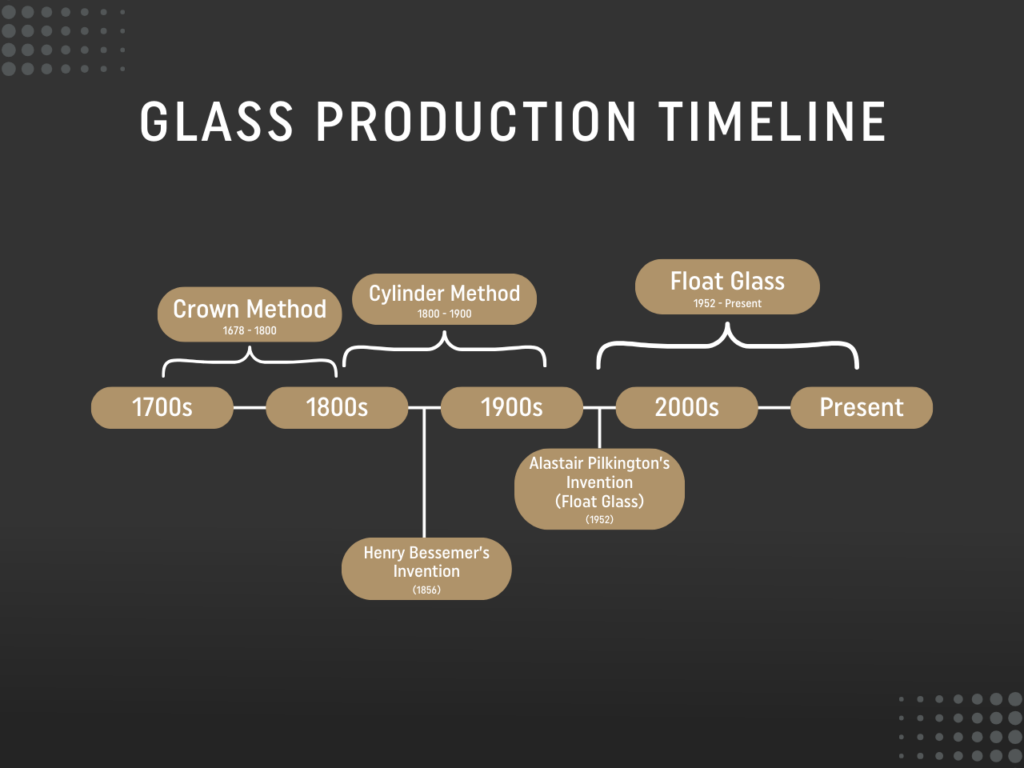

We have put together our very own timeline of the most impressive technological

leaps in glass production from the last few hundred years.

1700 – 1800s:

The arrival of the industrial revolution brought significant transformations in glass

manufacturing. For many years, glass had been manufactured through a

glassblowing technique which has its roots in the Roman Empire. From this came

crown glass, an immensely popular method of manufacturing glass for windows.

Glass was blown into a “crown” or a hollow globe, then reheated to be flattened into

a flat disk of clear but slightly distorted glass before being cut to the size required. As

the finished product was a circle, cutting square panes out of it made crown glass

one of the more wasteful methods.

The thinnest part of the glass was at the edge of the disk, with the glass becoming

thicker and more opaque towards the centre. This thicker, central part was often

used for cheaper windows. As a way of getting more of the best glass to fill a

window, small diamond shapes were cut from the edge of the disk and fitted into the window frame in the form of lattice work.

1800 – 1900s:

A similar but slightly more innovative method called the cylinder process was

commonly used during this period. It starts once more with a blowing technique.

Glass makers would blow a ball of glass at the end of a pipe and then shape it into a

cylinder by reheating it in a furnace and swinging it until it stretched into a cylinder

shape. They would then cut the cylinder open, flatten it, and cut it into panes. As the edges of the glass panes were already straight, they didn’t need to be cut out of the

sheet itself, meaning far less waste was produced than with the crown method.

You can spot evidence of this skilled craftmanship today, in buildings with old

windows made up of small rectangular panes.

1840s:

Let’s narrow down to a more specific point in time now, the 1840s. A British engineer

named Henry Bessemer created a system that could produce a continuous ribbon of

flat glass by forming this ribbon between rollers. It was an expensive process

because the glass ribbons didn’t come out perfectly smooth which meant the

surfaces needed polishing. While the system was innovative and did indeed pave the

way for the future of glass sheet production, it didn’t quite take off at the time. But

variations of this method were experimented with for almost the next 100 years.

1950s:

In 1959, after 7 years of experimenting with his R&D team, British engineer Alastair Pilkington developed the first successful commercial application for forming a

continuous ribbon of glass using a molten tin bath. Exactly what he thought when the

idea came to him is disputed, but what we can be sure of is what he was doing at the

time – washing dishes! Whether it was a plate floating in the water, or oil sitting on

the surface of it, something made him wonder, “What if glass floats on liquid?”

And so the idea of molten glass on molten metal was born. In this method, the glass

is melted down and floated on top of a bed of molten tin. It is shaped and formed by

rollers on either edge of the ribbon. This technique results in smooth glass on both

sides that does not require polishing. It revolutionised the industry and is now how

glass is made for cars and buildings all over the world. This float glass process is

also commonly known as the Pilkington Process.

The float glass process produces perfectly flat, smooth, straight sheets of glass

partly in thanks to the rollers which grip the sheet on either side and pull it to the

shape required. But this isn’t done automatically. Nowadays, the molten glass is

monitored constantly via cameras and a centralised control room. Operators then

adjust these rollers to achieve the desired finish. For a timeless method that has

remained largely unchanged since its initial conception and development, there is

arguably some room for innovation. Perhaps even some automation.

And that is exactly what Scorpion Vision did for a global glass manufacturer. Take a

look at our case study to see how we did it.